The Art of Scent 1889-2012 Curated by Chandler Burr

The Museum of Arts and Design, New York

The Art of Scent 1889-2012 Exhibition Catalog

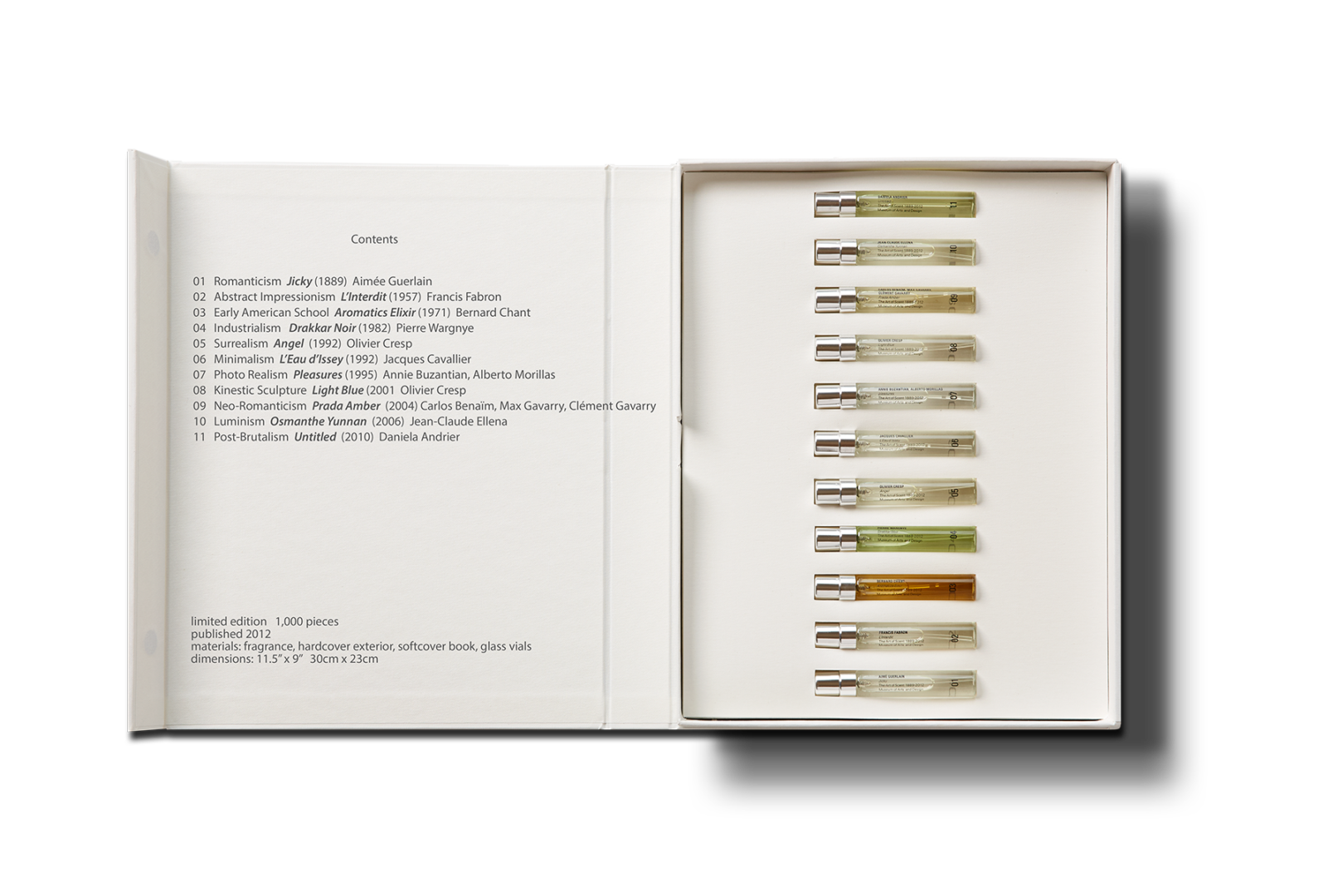

The exhibition catalog of The Art of Scent 1889-2012 at the Museum of Arts and Design's Department of Olfactory Art, curated by Chandler Burr. The catalog is a limited edition of 1,000 pieces. It contains the works of scent art exhibited in the show in printed glass vials, with a softcover book of eleven essays written by Burr and placing each of the works in historical context.

Contents

limited edition 1,000 pieces

published 2012

materials: fragrance, hardcover exterior, softcover book, glass vials

dimensions: 11.5” x 9” 30cm x 23cm

6

“The genius of Jicky is that it could never have existed in nature. Guerlain had created both a new work of art and a new art form.”

THE ART OF SCENT 1889-2012

01 Romanticism

Jicky 1889

Aimé Guerlain (1834–1910)

Lent by Guerlain

Aimé Guerlain was one of the most important olfactory artists of the 19th century, for the simple reason that he, along with the perfumer Paul Parquet, effectively invented olfactory art.

Guerlain was born into an era of rapidly advancing technology and shifting artistic styles. Haussmann gaslights were changing the cityscape and turning Paris into the glittering bourgeois society in which Guerlain worked and upon which his art had a profound impact.

Guerlain’s wealthy family was already famous as scent makers, but with the creation of Jicky he altered the medium itself.In 1884, Paul Parquet was the first to use a synthetic raw material in developing Fougère Royale, and five years later Guerlain used three synthetics—

the terpene alcohol ß-linalool, the molecule 2Hchromen-2-one commonly known as coumarin), and ethyl vanillin— to create Jicky. These synthetics freed olfactory artists from the limitations of nature in the same way that new metals had freed Gustave Eiffel from traditional materials in building his tower, which was completed in 1889, the same year that Guerlain launched Jicky.

All art is artificial. It must be. The artist, in every medium, uses materials to manipulate, to create a concept, saying to the public, “I will make you feel this. I will make you perceive that.” The artist creates works to generate fear or rage, disgust or reverie, unease, joy, or pity. The more ingenious their false representations, the more intensely they are felt.

The genius of Jicky is that it could never have existed in nature. Guerlain had created both a new work of art and a new art form. Edgar Degas, who was born the same year as Guerlain, once remarked to a landscape painter: “A vous, il faut la vie naturelle, à moi la vie factice” (You need the natural life, I the artificial). This concept was not only crucial to the legitimacy of scent as an artistic medium. It was also a defining quality of the late 19th-century art world.

12

“Wargnye made dihydromyrcenol the structural core of Drakkar Noir and by so doing transformed olfactory art as deeply and radically as industrialization changed any of the arts.”

THE ART OF SCENT 1889-2012

04 Industrialism

Drakkar Noir 1982

Pierre Wargnye (b. 1947)

Lent by L’Oréal and International

Flavors & Fragrances

Laundry detergents made of synthetic surfactants were first mass-marketed after World War II, and detergent use at home skyrocketed. But there was a problem. The detergents themselves smelled terrible, so perfumes were created to mask their odors.

The task of creating a scent for the detergents was a difficult one. The molecules used in detergents were harsh, because they were designed to break down other molecules, but expensive scent materials could not be added because consumers would not accept the price jump. However, an American laboratory synthesized an inexpensive molecule called dihydromyrcenol, which had a very strong smell that resembled nothing else. (No two molecules ever smell exactly identical.)

would equate the molecule on a visceral level with clean laundry, in the way that they equated red with stop.

In the late 20th century, architects and composers were using industrial forms and sounds, and painters were producing functional images. To olfactory art, Wargnye added industrial molecules.

In 1982, he used dihydromyrcenol as the structural core of Drakkar Noir. Combining functional materials in fine fragrance was, to some, a sacrilege. It was also potential suicide. Who, Wargnye was asked, wanted to smell like clean laundry? That hundreds of millions of people wanted to smell like clean laundry was not a surprise to any observer of art in the 20th century.

Wargnye was engaged in the project of democratizing art, and in doing so he transformed the olfactory art as deeply and radically as industrialization changed any of the artistic mediums.

24

“Ellena has built a translucent sheet of scent that collects and re-emits light. It is a consummate work of virtual silence and calm that creates an immense presence.”

THE ART OF SCENT 1889-2012

10 Luminism

Osmanthe Yunnan 2006

Jean-Claude Ellena (b. 1947)

Lent by Hermès

There is no more overtly intellectual olfactory artist working today than Jean-Claude Ellena, nor one who has worked more successfully in such an extraordinary number of stylistic modes. He has experimented with several very different aesthetic schools, starting with the late 19th-century Romanticism of First (1976). His body of work then ranged from late 20th-century Hyperrealism (In Love Again) and 21st-century Abstract Expressionism (Ambre Narguilé) to contemporary Figuritive style (Terre), Surrealism (Bois Farine), and Luminism (Eau de Thé Vert).

Eau de Thé Vert (1993) is not, despite its name, a Realist presentation of green tea.

It is, rather, a concept of tea (neither green nor black), hovering between a pure intellectualization of its subject and its presentation as a real-world object.

A decade later, Ellena created another great work of Luminism with L’Eau d’Hiver, taking an old synthetic, aubepine, and building onto it a natural honey absolute, together with methyl ionone (a molecule that gives the idea of iris) and the milky-musky synthetic MC-5. Ellena spent two years on L’Eau d’Hiver, in which he used twenty materials. It is, he says, “the idea of the diaphanous,” an effect realized in part by the olfactory milky gauze of aubepine and MC-5, which overwhelms our vision but has no solid core.

Osmanthe Yunnan, created two years later, is a masterpiece of the genre. As in all of Ellena’s works, its structure is so meticulously crafted and its technical virtuosity so palpable that they become part of the work’s aesthetics. Ellena has built a translucent sheet of scent that collects and re-emits light. It is a consummate work of virtual silence and calm that creates an immense presence.

26

“With Untitled we feel the violence of a cold storm that has ripped limbs from young trees, revealing the organic material inside, the smell of fresh cold rain water, the green of a chilled spring, heightened and slightly brutal.”

THE ART OF SCENT 1889-2012

11 Post-Brutalism

Untitled 2010

Daniela Andrier (b. 1964)

Lent by Maison Martin Margiela, L’Oréal and Givaudan

Olfactory mass, power and force – which the adept scent artist can separate and manipulate individually – have always been aesthetic properties, but they have not always been used with skill. Before World War II, when the use of synthetics had not yet given olfactory artists great control over their materials, many scents were strong in the same sense that traditional glass was heavy. It was simply the nature of the material. Like the new glass of the 20th century, which was stronger, clearer, and lighter and could be used by architects in many innovative ways, the astonishing molecular fractionations of natural CO2 extractions and certain concentrations of synthetics gave scent artists actual molecular-level control of their creations and a freer rein to their imaginations.

It was not until the late 20th century that olfactory artists moved the medium to a Brutalist extreme and fully embraced the man-made. Odeur 53, created by Anne-Sophie Chapuis and Martine Pallix, brilliantly and daringly embodies an aesthetic that is completely synthetic and industrialized, an uncompromising work that overtly taunts the wearer. It is an olfactory painting of charred metal, raw electricity, chemicals, synthetic fibers, and smoking car tires. Odeur 53 is not merely a work whose entire aesthetic is concerned with impact. It gives the impression of having eliminated nature altogether.

Daniela Andrier’s Untitled is an extraordinary creation, because its structure is designed with all the stylistic elements of Brutalism, and its aesthetics generate a mixture of

excitement and unease. But Andrier used this mass of raw power while returning us entirely to nature and the natural world and built Untitled primarily with galbanum, a natural plant resin. With it she built an abstract, roughly textured olfactory concept of green. With Untitled we feel the violence of a cold storm that has ripped limbs from young trees, revealing the green organic material inside, the smell of fresh cold rain water, the green of a chilled spring, heightened and slightly brutal.