excerpt from The Perfect Scent

Jean-Claude Ellena | Hermès

At the time Hermès began courting him to become its in-house perfumer, Ellena was just completing a perfume called L’Eau d’Hiver, the third (and, given his entry into Hermès, obligatorily the last) of a trilogy of perfumes he’d made for an exquisite, in fact all-but-revolutionary niche collection, Editions de Parfums run by a scent impresario named Frédéric Malle. Ellena’s approach to the construction of L’Eau d’Hiver reveales the technical and intellectual approach he had at this point in his career evolved.

He began his perfume by intellectually reconceptualization the great Guerlain classic Après l’Ondee. “The problem,” he started and then immediately checked himself. “Well, you can’t say there’s a problem with Après l’Ondee, but… bon, voila: They were too opulent, these Guerlain in the baroque, super-charged tradition of voluptuousness. ‘J’en mets, j’en mets, j’en mets.’ ” I put in, I put in, I put in. “At the same time, there’s the Guerlain sillage.” Sillage is the scent wake the perfume’s wearer leaves behind in a space, an olfactory infrared arc of their trajectory, and is a technical aspect of a scent that the perfumer must skillfully engineer. I believe it was the perfumer Calice Becker who once defined sillage to me, somewhat metaphysically, as the sense of the person being present in the room after they have left. “It’s marvelous,” said Ellena, “this gauzy veil that envelopes you. So I wanted to find this sillage, but in enlightened form. My style is perfumes that are at once light and very present.

“So for L’Eau d’Hiver I took my inspiration from Après l’Ondée’s theme. Cloud. Soft, comfortable, light, and very present, but without all this—” he gestured “—grosse étoffe that you have with the Guerlains, all this stuff. It took me forever to do it. The idea of the diaphanous.” He conceptualized sleeping in hay in the summer. Heat. Sun. A powder that envelopes without weight. He began the perfume’s construction with a gorgeous absolute of hay, one of the most sublime of all perfume materials. Hay is, as literally as possible, the smell of liquid summer sunlight. He wanted to create with it the scent of a cloud filled with sun. People expected l’Eau d’Hiver to be a cold water (the name means “winter water”). In fact, he was building the opposite, a hot water for a cold winter. Starting with hay, he took an old synthetic, Aubepine (an anisic aldehyde), that smells a mix of the finger paint you used at age five plus the cleaning wax applied to formica floors. Aubepine costs almost nothing, around €3 /kilo. He bolted those to methyl ionone (a synthetic that gives the idea of iris), the milky-musky molecule MC-5, and a natural absolute of honey. It took him two years to fine tune this engine, Malle giving him creative feedback, the two of them going back and forth, and in the end, his formula, according to Ellena, totaled twenty ingredients, relatively minimalist for a perfume. L’Eau d’Hiver smells of ultra-fine ground white pepper and extremely fresh, cold crab taken that instant from the ocean. It is a brilliant, marvelous, utterly strange perfume, truly unique—it references nothing—and among the greatest ever created.

Véronique Gautier appreciated this maximalist minimalism. As a Creative Director (the role she played at Hermès), Gautier was ahead of the game in several ways. She understood, as some did not, that one could stuff a perfume like a sausage with the most expensive ingredients in the world and wind up with carefully macerated shit that cost a fortune. What mattered was the way the thing was built.

Gautier was after great art, and great art is great artifice and great manipulation that forces its experience on the viewer, tells him its story, and thus changes him. Ellena was an artist. That’s why she wanted him. And Gautier would also tell you instantly that Ellena wasn’t there to recreate nature. As an artist, he was principally an illusionist, a description he agreed with emphatically. “Picasso,” Ellena liked to say, “said, ‘Art is a lie that tells the truth.’ That’s perfume for me. I lie. I create an illusion that is actually stronger than reality. Some people are surprised when I say this, but: sketch a tree, and it’s completely false, yet everyone understands it, and actually if you do a very, very basic sketch, abstractly, people will understand it better than if you do every single leaf. Give them too much, and people will start to say, ‘OK, it’s a tree, but is it an oak or a maple?'” He thus practices a perfumery of very few ingredients. And, he would tell you, the greater a perfumeur’s power over his art, the greater his mastery of such illusion.

Ellena will dip a touche into a molecule called isobutyl phenylacetate, which smells vaguely chemical and nothing else, and another into a synthetic molecule whose common chemical name is ethyl vanillin. (A rich gourmandy vanilla molecule, its IUPAC name is 3-methoxy-4-hydroxy benzaldehyde, and it is the heart of Shalimar.) He puts the touches together and hands them to you. Chocolate appears in the air. “My métier is to find shortcuts to express as strongly as possible a smell. For chocolate, nature uses 800 molecules, minimum. I use two.” He hands you four touches, vanillin + natural essences of cinnamon, orange, and lime—each of these has the full olfactory range of the original material—and you smell an utterly realistic Coca-Cola. “With me,” says Ellena, “one plus one equals three. When I add two things, you get much more than two things.”

He will hand you a touche that he has sprayed with a molecule called nonenol cis-6, which by itself smells of honeydew melon or fresh water from a stream. He’ll then hand you a second touche with a natural lemon on it, direct you to hold them together now, and suddenly before you appears an olfactory hologram of an absolutely mesmerizing lemon sorbet.

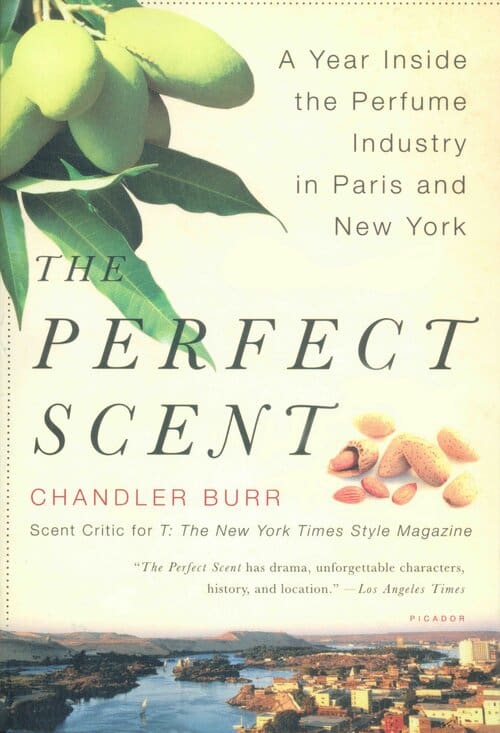

The explicit point was not to create a thing but an illusion of that thing, an olfactory alchemy. The point of Nil was not to create a green mango but the illusion of a green mango.

He was in his lab. It was June 11. Ellena began the work of changing AD2.

As do virtually all perfumeurs, Ellena works in his office at his desk, running molecules through his brain as he stares out the window, jotting down the ideas, 10ml of this, 20 of that. He sends these down the hall to his lab technician, who assembles them, brings them back, and sets them before him. He smells this, the assemblage he imagined, and frowns irritably or laughs with delight and surprise or narrows his eyes in fury or frustration. And then he adds x ml of other materials to another formula on his computer screen and with the push of a button sends those off to the lab.

Like young French chefs dutifully imbibing the culinary cannon—with the basic mise en place (flour + butter + cream + stock) you master the basic white sauce—all young perfumers can recite in their sleep the recipes for the classic categories. Ellena had learned them at a tender age.

How do you make a basic chypre? Answer: patchouli + ciste labdanum (a species of shrub; its scent is bizarrely animalic, like the fur coat of an unwashed muskrat) + mousse de chene; bergamote as well, if you want.

How do you make an amber? Labdanum + vanillin.

Junior perfumers discover that Vetiver Huile Essentielle from Haiti smells like a Third World dirt floor and Vetiver Bourbon from Isle de la Réunion smells like a Third World dirt floor with cigar butts. (They hope to do something wonderful with the cigar butts.) They learn, as Ellena knew from decades of work, how to create the illusion of the scent of freesia with two simple molecules, both synthetics: ionone beta + linalool. And orange blossom: linalool + anthranylate de methyl, which by itself smells like aspirin. The classic Guerlain perfumes often used a molecule called styrex, which smells of olive oil pooled on a table in a chemical factory. Add phenylethylic alcohol and you get lilac. Add the smell of corpse (indoles), you get a much richer lilac. And you can give your lilac, freesia, and orange blossom a variety of metallic edges: Add allyl amyl glycolate, you get a cold metal freesia. Add amyl salycilate, and you get a freesia with the smell of a metal kitchen sink dusted with Ajax powder. Aldehyde C-12 lauric adds an iron with a bit of starch still on it.

A small but increasing number of perfumery raw materials are controlled substances—you see “USDEA” and a warning on the label—because they are the precursors for making drugs: methamphetamine and others. Security measures are taken, in particular at the larger companies because by definition they have larger amounts of the stuff sitting on shelves and, as one lab tech put it to me, perfume labs are potential crystal meth labs.

By Ellena’s rough estimation, the changes Gautier and Dubrule had asked for involved inflecting between 5 and 25% of the formula. The estimate hardly mattered; it would depend on a thousand things, and anyway he wouldn’t know for sure till they’d reached the final perfume. Ellena assembled the extant AD2 on a fresh standard formula sheet, briskly listing each material, its product code, its precise amount in ml, and its price per 1000 ml. Together the materials totaled 100% of the formula.

He spent some time eliminating the tranchant bitter acidic ingredients, then corrected the proportions. Then he sat at his desk and stared at the formula.

He started with Hedione, which has a jasmine scent. Hedione (its more formal name is dihydrojasmonate) is a molecule that was found by [TK was engineered by??] mucking around molecularly in jasmine, and it is a material Ellena loves. He then put in anthranilate methyl extra 10% DPG, Iso E Super (a synthetic with a light woody scent used prominently in Beautiful by Estée Lauder and Calvin Klein’s Eternity), and a natural essence of Neroli. As a solvent, ethyl alcohol is used for perfumes, but here Ellena used dipropylene glycol because, due to archaic European regulations, the concentrés of perfumes can’t be transported from place to place if they have alcohol in them.

He tried three different iterations, smelled them, and didn’t like them at all, so he tried four new directions, which Monique, his lab tech, mixed and lined up neatly on his desk in tiny vials. He labeled the touches with a pencil, AD2, AJ1, AJ2, AJ3, dipped each, and held the four spread like a hand of cards in poker.

He leaned over in his chair, closed his eyes, and smelled each systematically. He grimaced thoughtfully. He bent each of the touches crisply, re-smelled each systematically, precisely two seconds per touche, then reversed back down the line. Murmured, “C’est pas vrai….”

AJ2 was the freshest, AJ3 the most mango, sweet, AD2 the most lotus. He lowered the grapefruit synthetic in all of them and then added to all except AJ3, in different proportions, hexanal trans 2, a synthetic that smells half of golden apple, half elementary school glue paste, because he wanted a greener fruit. He inflected AJ4 with 5 out of 10,000 parts of ambroxide, an extremely expensive synthetic derived from clary sage that had been molecularly futzed with. The ambroxide was for Gautier’s fond, in theory, although personally Ellena thinks the olfactory pyramid, the cliché glossy diagrams of top, middle, and bottom notes salespeople mechanically deploy at Macy’s perfume counters, is “complete bullshit. I’m sorry, you add something to the bottom and you influence the top notes, and when you first smell a perfume you smell everything, top to bottom, instantly.”

(As an intellectual exercise in what one must not do, he added C-14 aldehyde to AJ5. Aldehydes, synthetics created in the 1880s, are the secret to Chanel 5 and can smell of wax, citrus, or peach flesh. As he suspected, AJ5 was now a rich peach that in its lusciousness completely drowned the green freshness.)

His cell phone exploded on the desk and he jumped, grabbed it and glared at the number. Brightened instantly. “Ah, c’est Gautier!” Answered with a grin and an insouciant solicitude: “Oui, madame la présidente.” They chatted. He clicked off, put the phone down, and stared out the window.

Monique brought the new iterations and he dipped and smelled. Smelled them again. Tossed the touches on his desk and sat back. “Ambroxide helps the tenacity,” he murmured to the window and scowled. He picked up one of the touches again and smelled it and moved his torso back and forth very, very slowly, forward, back. Tossed the touche on the desk and looked at the ceiling and smiled a small dark smile. Unconvinced, perhaps. Or perhaps waiting for a material to fall from the sky. Monique brought an envelope. An invitation from a very expensive luxury goods maker. Black tie. He looked at it, chanted out loud, “Monsieur this-and-that, Madame this-and that would be ravished to have the company of Monsieur Ellena…” He tossed it aside. “I rarely go to those things. I’m not a sophisticate.” (Un homme mondain.) “I go, I feel like a penguin.”

He smells his iterations again. “At the moment,” he says, “I like AJ3. It’s the freshest.”

~

Sarah Jessica Parker | Coty

On November 22, 2005, when serious winter has already set in on the city bringing battleship gray clouds, intermittent cold rain, and a chilled wind off the metallic Hudson, the first creative meeting on Sarah Jessica Parker’s perfume product is held at IFF’s global headquarters, 521 West 57th Street.

It is 3:00pm and you’d think it was 6:00, or maybe 8:00. It’s ambiguous, and at mid-afternoon the cars already have their headlights on. 521, which sits opposite the New York CBS affiliate, is a paradigmatic massive nondescript office structure with 1980s gold-colored doors, Donald Trump meets East Berlin. Catherine Walsh and Carlos Timaraos are at 8th Floor reception. Several IFF people are gathering as well because Parker is arriving. (One says to me discretely, “It’s not my project, but I really like Sex and the City”).

Everyone goes downstairs to wait for her. Joanne H. Trembley, IFF’s VP of Sales for North America is there, and Yvette Ross, IFF’s Senior Account Executive on Parker’s perfume. Walsh, wearing her signature bright-red lipstick and looking professionally chic, chats with Trembley and Ross and keep an eye on West 57th Street.

Exactly on time, a black Town Car pulls to the curb and stops, and we watch someone inside open the large rear door. Melinda Relyea, Parker’s assistant, a blond young woman who always seems laid-back and cool, gets out, followed by Parker. It’s always a bit of a surprise how thin and small she is. She is wearing stilettos and a trim gray camel’s hair coat with a belt tied precisely around it and, in the afternoon gloom, gigantic jet-black Ralph Lauren sunglasses that cover her face. We watch the chilly wind blowing her hair around. “Why is it so cold so early,” murmurs Yvette Ross to no one. Parker comes out of the gray into the warm lobby and we all start the greetings. She takes off her coat, and she’s dressed in a simple blue shirt and slacks. Some mascara and a bit of natural lip color. Her eyes are the same intense blue.

I sort of hang back a little, and when she gets done with the rest, she turns to me and for an instant we both hesitate there in the lobby. I realize she’s not certain what is appropriate either, but journalist or not I give her a kiss on the cheek. She smiles and says, “How are you?” with a voice that has a raspy/ squeaky angle. We all crowd into the elevator and someone hits the button.

The meeting takes place in one of the larger meeting rooms I’ve seen in the IFF complex, a glass-enclosed room surrounded by the offices of perfumers and evaluators. There’s a vast expanse of table, and we do that thing where everyone enters and chooses their places carefully. Ross, as the IFF account exec, directs Parker to the center (“Here?” says Parker, “you want me here?”). I find the chair nearest an electrical outlet, plug in my computer, sit down next to Walsh.

There are three sets of players here, three interdependent kingdoms.

Coty is arguably first among equals. It is Coty, in the person of Walsh, that allows all this to happen. The financial risk is theirs, and they are capitalizing the brand with millions of dollars in development, overhead, marketing, advertising. IFF is quite aware that Coty is its client. Everyone knows that Coty sent the brief to other scent makers and that Walsh chose the juice that IFF perfumers Laurent LeGuernec and Clément Gavarry had created—both of them are here as well—which is why IFF won the brief, and in this plush conference room the IFF people, in all the appropriate, subtle ways of corporate interactions, make clear to Walsh that they appreciate her business. LeGuernec is sitting next to Parker at the table, telling her about a scent angle he’s trying in a current, unrelated project. Gavarry is next to him, smiling broadly.

Parker is the concept, the commercial idea around which this particular Coty venture is built. Walsh is there because Parker is there, and it is Parker’s aesthetic that’s guiding all of this, and her artistic vision of the juice is what will be sold. She’s central to the commercial idea, but then Parker’s only in the room because Walsh said yes to her. And everyone is aware of the various roles that are being played and of who ultimately signs the checks. A few months before, Parker, with Matthew Broderick, spotted Walsh at a glamorous black-tie event at The Plaza. She grabbed Walsh by the arm and, somewhat to Walsh’s consternation, towed her around and introduced her to everyone she could corral as “my boss.”

“Don’t forget the sushi,” says Ross. Parker looks around, exclaims, “There it is!” There’s a table overflowing with cookies, drinks, salad, cheeses, fresh fruit (New York delis do great fresh fruit). Some of us takes plates, pick up tongs. “All during the creation process of Lovely,” Walsh explains, “every time we met we had Sarah Jessica’s favorites, sushi and popcorn.” Someone sets down a large bowl of popcorn. I put two pieces of maguro on my plate. “And it’s the good stuff,” says Timaraos, who is behind me. (It is, indeed, the expensive stuff.)

We reassemble at the table. People are chopsticking up pieces of raw clam and rice, the IFF contingent is organizing notes, and Walsh and Parker avidly discuss Parker’s recent appearance on Oprah’s once-a-year Favorite Things show. “It’s the things that get her through the day,” Parker says, “from the necessary to the completely indulgent, soaps to slippers to Tivo. Last year,” she adds, “it was all teachers.”

“This year it was all Katrina workers,” says Walsh.

“And she picks one of her favorite things and gives to everyone in the audience,” says Parker. “And she picked Lovely!” The big deal with Oprah is if she’ll say the name of the product, and Parker tells us about her best friend Jill who called her and said (she puts on a thick NY accent), “Did you see it?! Did you see it?! If she said it once she said it five times!”

“She asked me afterwards,” says Walsh, of Parker, to the room, “how it had gone, and I told her that if Oprah had simply said she had a new fragrance, I’d have been happy. The fact that Oprah, who doesn’t wear fragrance, said this is her favorite scent, and that she wears it, is amazing!”

It happened days ago, and they’re still elated.

It’s Parker who claps the meeting to order. “OK! What are we doing today?”

There’s a three-part agenda. First, a “what’s this new product going to be about” discussion combined with a business update on the state of the brand. Second, a crash course for Parker in cosmetic chemistry; after years in the industry Walsh and Timiraos generally know stearic acid from propylparaben, but Parker does not, and as they’re going to be creating a perfume product (they’ll be determining what kind) in a rather unusual base, they want her to be comfortable with propylparaben as well. Third is giving Parker a little course in Perfumery 101.

Walsh sits forward, and the room turns to her. “I think it’s important to go over what we were trying to do when we created the Sarah Jessica Parker brand,” she begins. “That this scent would not be created like other celebrity fragrances. We [at Coty] were the masters, the starters of the celebrity fragrances.” She looks in turn at each person. “We learned that with other celebrities you have to launch something every three months. But here we wanted something that was the opposite of what people had seen in Sex and the City.” Parker is watching Walsh attentively. “Sarah Jessica was provocative in that series. Here with her fragrance, it’s different. We wanted her perfume to possess a sense of quiet. An understated elegance.”

Parker says, “A trust in the audience. That assumes, as good television does, that they’re smart.”

Ross and LeGuernec are taking notes.

Walsh puts the first big point on the table. “What we’re doing today is not—” (she stresses the not) “—coming back next fall with a Sarah Jessica Parker flanker.”

“Flanker” is the industry term for a new version of an exisiting perfume. Polo is a hit; Ralph Lauren puts out Polo Blue. Privately the perfume industry views flankers the way the movie industry views sequels; like later Star Wars episodes, they enjoy rather lesser reputations. Financially, however, they have a logic, though sometimes the flanker happens because the original was a success, sometimes because it was a failure: Chanel did Egoiste, which disappointed, but having invested so heavily in the name it did Egoiste Platinum, which succeeded. Often flankers are dictated by the investment in the name. Yves Saint Laurent put a jaw-dropping amount of money in M7 (the name stands for “the 7th YSL masculine”) created by star perfumers Alberto Morillas and Jacques Cavallier of Firmenich. M7 smells like a Fiat engine engulfed in flame on a shoulder of the A6, an alarming chemical storm of burnt rubber, charred metal, torched leather, and toxic melting polycarbon. This is not necessarily a criticism: It was a well-constructed, thoughtfully built car in flames. But people stayed away by the million, and the scent was a disaster. YSL allowed some time to go by, then launched the M7 flanker, M7 Fresh. M7 Fresh, also by Morillas and Cavallier, is an excellently constructed light smoke scent, relieved of the flame-thrower death smell and in all ways better than the original. (It too failed to sell, however, and Yves Saint Laurent has now, in the best Argentine manner, very quietly disappeared both scents.)

Flankers are supposed to be variations on a common theme, but the only thing Eternity and its flankers have in common are the ad dollars Calvin Klein marketers spent on imbedding that name in people’s neurons. Dior is king of the flankers with its Poison franchise. Poison of 1985 was followed by Poison Tendre, Poison Hypnotique, and, in 2004, Pure Poison. I once asked a Dior exec, What is the commonality between the Poisons? “None,” he said. “None! Well—” he reconsidered it “—all have white flowers,” and then he listed the flowers, which bore no similarities. I said: In other words, none. He said: “Correct.” Flankers differ from seasonals in that flankers are permanent (i.e. they’re allowed to live as long as they sell) additions to the house’s collection whereas seasonals have death sentences built into their designated lifespans. (Seasonals are mostly issued for summer and are basically excuses for the house to bring out lighter, more commercial perfumes.) Escada is the king of seasonals. Puig, Escada’s licensee, terminated Ibiza Hippie, a summer seasonal with a flanker-sounding name. It was a terrific little commercial jewel, and deleting it was a minor crime.

Walsh wants Sarah Jessica Parker’s Lovely to be what Parker wants it to be: a classic, a serious, elegant perfume for adults. The dilemma is that they also want to put out a new product that reincarnates Lovely, this perfume they’ve worked so hard on, and to the market, that says flanker, but Walsh is determined somehow to produce a sequel that is an original at the same time. She is saying to them that they are going to walk this tightrope, and they’re going to walk it successfully. The question is how. “We want an initiative other than a flanker,” says Walsh. She emphasizes the words, looking at each of them, and the table is rapt. “This product we start working on today is not about changing Lovely in any way. This is about using Lovely to give the customer something different. It will have the same olfactive heart of Lovely, but it’s going to have to be big enough and strong enough to stand entirely on its own. We have nice ancillaries in the line. This has to be perceived by the customer as just as important as the first launch [of the perfume], yet keeping the fundamentals of the scent.

She pauses. “Remember that Sarah Jessica created her scent from scratch, from components in her head, with a very particular vision, a scent that smelled of skin, and there’s something in your concoction—and I use that word as lovingly as possible—that is far from what we put in that bottle. That something is what we’re going to find today. That something is our product.” That, in short, is why this thing they’re starting right now will stand on its own. The same perfume, but with a different aspect of its soul made visible.

She turns to Parker. “Remember how you said it was too dirty, so we flowered it up, and you said it was too flowery.”

They both laugh.

Parker: “Too chaste.”

Walsh: “Too fat.”

Parker: “Oh, god!”

Walsh: “And we got to something that is so clearly you and so clearly your vision but that simply worked better as your first scent. Better for your audience.”

Parker nods.

Walsh: “But still there’s something you’re not getting out of this scent.”

“Something,” Parker turns to me and carefully stipulates, “that we agreed not to get. Knowingly not getting it. There was a certain fattiness that brought down the higher notes and a bit of dirtiness. And honestly—” (she turns to them now) “—I don’t think that would have been right.”

Walsh says to me: “Think of it this way, Chandler. The component of Sarah Jessica’s original concept that carried the most character was the African oil, which brought the fattiness, the human skin, the other too things brought smoke-plus-dirt and, then, the girl.” To Parker: “When you lose that oil, you just lose that skin aspect.”

Parker: “The perfume just gets higher!”

Timaraos says to the room, “We felt that oil was the best starting point for this re-interpretation of her fragrance.”

“So lets’ not take our eye off Lovely,” says Walsh to everyone. “Let’s return to our original story but create something technologically that went missing with that original oil. Because it’s Sarah Jessica, we’re going to be launching at the busiest time of the year, but this project can’t be, ‘Here’s a nice little gesture.’ It has to be a big idea. Not an ancillary or a soft launch. We are totally trying to do something that the market is not doing. We presented this to Michele [Scannavini, President Worldwide of Coty Prestige] and Bernd [Beetz, CEO of Coty, Inc.], and they’re totally behind it.”

Walsh pauses. Everyone is listening intently. “Great,” says Parker, focused on Walsh.